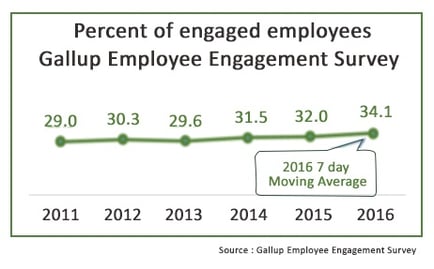

After years of studies, surveys, and billions of dollars spent on employee engagement, Gallup’s headline in 2015 was “Employee Engagement in U.S. Stagnant in 2015.” We see a slight uptrend, and when we add in the 7-day moving average of November 28, 2016, a chart shows a 5% increase over five years.

If employee engagement is the holy grail of employee statistics, is 1% per year improvement a trend worthy  of notice? Impossible to know without knowing the details. If the benchmark surveys we see are a sign, a few companies are making good progress but the rest are not.

of notice? Impossible to know without knowing the details. If the benchmark surveys we see are a sign, a few companies are making good progress but the rest are not.

Employee engagement has always seemed “fuzzy” to us. In our corner of the human capital management world, we work on solutions to business problems defined at the outset of a project, measured by impact on our partners’ KPIs.

Pausing now to think and write about engagement, we believe perhaps the fuzziness is caused by ambiguous definitions and a misguided approach. What the term means seems to depend on who you ask.

- Bersin defines employee engagement as an employee’s job satisfaction, loyalty, and inclination to expend discretionary effort toward organizational goals. We trust Bersin, but those perceptions depend on the relationship with the employer. It’s as though we measuring the employee’s head to see if the employer is doing the right things.

- Gallup says workers are engaged when they have “an opportunity to do what they do best each day, having someone at work who encourages their development and believing their opinions count at work.”[1] Once again, these are not employee issues—they are management problems.

- CustomInsight’s definition is “the extent to which employees feel passionate about their jobs, are committed to the organization, and put discretionary effort into their work.”[2] Comparing that to Bersin and Gallup, we get commitment and discretionary effort, but passion? Is that really the right word? When you look it up in a dictionary, it seems a bit out of bounds.

Only when we go back to the origin of the term do we find an explanation for the disconnect. William A. Kahn, writing in the Academy of Management Journal, first described engagement in 1990:

“People can use varying degrees of their selves: physically, cognitively, and emotionally, in the roles they perform, even as they maintain the integrity of the boundaries between who they are and the roles they occupy. Presumably, the more people draw on their selves to perform their roles within those boundaries, the more stirring are their performances and the more content they are with the fit of the costumes.”[3]

The disconnect for us is that too often the concept of employee engagement attempts to reduce employee sentiment to single cipher. Every human being is a complex individual who “engages” or “disengages” in varying degrees throughout the work day, depending on the role and the people with whom they interact.

What started us on this line of thinking was studying Douglas W. Hubbard’s universal approach to measurement, described in How to Measure Anything (Wiley 2010).

- Define a decision problem and the relevant uncertainties. The first question is not how to measure, but “what is your dilemma?”

- Determine what you know now. Quantify the uncertainty about the decision you need to make in terms of ranges and probabilities.

- Compute the value of additional information to identify what to measure and inform us on how to measure it. (If no information values exist that justify the cost of measurement, skip to step 5.)

- Apply the relevant measurement instruments to high-value measures: random sampling, controlled experiments, and other methods we can use to reduce uncertainty.

- Make a decision and act on it.[4]

In Hubbard’s approach, measurement starts with defining a decision, but what the decision should be is often not obvious. Hubbard likens it to measuring project performance to track project progress. It’s a circular statement. The right question is what would we change if we knew more about the project’s progress.

Skipping this step is like conducting an employee survey without knowing what information we want or how we are going to use it. When we go inside engagement surveys and examine the questions, we get information, but do we know what we are going to do with it?

Conclusion

We understand from benchmark surveys that companies with high engagement enjoy better productivity and profitability. If we define the objectives as productivity and profitability, what decisions are we trying to make? We are not asking the right question.

We know a lot about human behavior and what motivates people. If we are aware employees are more engaged in their work when they believe their opinions matter, what action would we take if certain employees did not believe that?

That is the place to start. It’s a specific business problem, and we can use it to gather data to form hypotheses for decisions we need to make. And that is right in the middle of our comfort zone.

References:

1. “Employee Engagement in U.S. Stagnant in 2015.” Gallup. January 13, 2016.

2. Custominsight.com. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

3. Kahn, William A. "Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work." Academy of Management Journal; December 1990, Vol. 33, No.4, 692-724.

4. Hubbard, Douglas W. How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “INTANGIBLES” in Business. John Wiley & Sons. Hoboken, New Jersey, 2010. pp 73-74.

Pixentia is a full-service technology company dedicated to helping clients solve business problems, improve the capability of their people, and achieve better results.